Every day passes by with so many interesting, random historical facts that go unnoticed by many. Today is no different, as today is the anniversary of the first presidential veto!

The veto power was subject to an extensive debate in the Constitutional Convention. Although several states had given their governor veto power, they varied in how many votes, if any, could override a veto. At the Constitutional Convention, there was heavy debate over whether the veto should be as powerful as the King’s, which is absolute, or if he should even have the power. Ultimately, they decided on a compromise where the President was given the power to veto legislation but it was subject to a two-thirds override by Congress. In Federalist Paper Number 73, Hamilton explained that this power provided the President independence from Congress while providing him with the power to check a Congress interested in factional issues. Meanwhile, Congress could reverse the President if the measure supported widespread support.

When the President vetoes a bill they have two options: a real veto or a pocket veto. When the President exercises a real veto, they return the bill to the Chamber of Congress it originated in with the reasons why he doesn’t support it. These are subject to a veto override. Meanwhile, if Congress is adjourned the President can use what’s called a pocket veto, where they merely refuse to sign it. Since Congress is adjourned, the President cannot return the bill to the chamber it originated in, and therefore, a pocket veto is not subject to an override. In modern times, Congress does not adjourn until a new Congress is sworn in so there are few pocket vetos. The last use of the pocket veto was on December 19, 2000, by President Clinton.

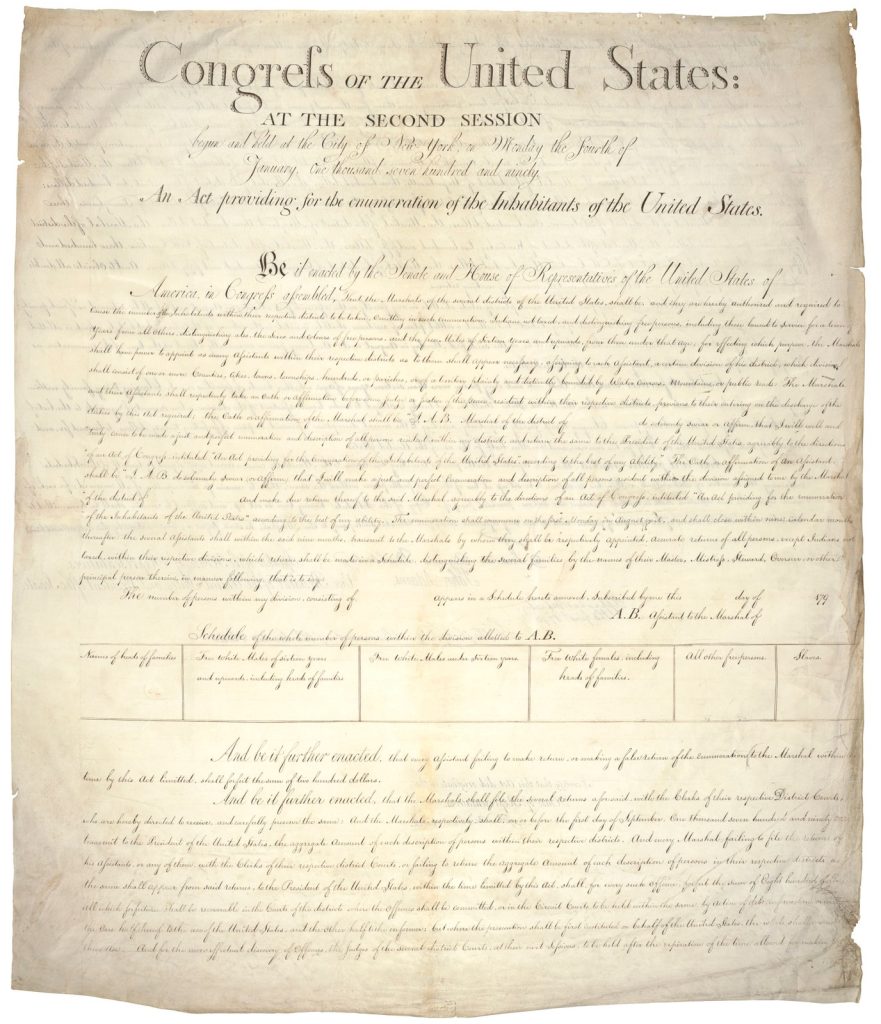

The Constitution stated the number of representatives each state should have until a census could be conducted and until Congress passed a law giving each state a different number. Congress did just this by passing the Apportionment Act of 1792. However, when it was presented to President Washington on March 26, 1792, his cabinet was deeply divided over the bill. Jefferson and Randolph were concerned that Congress unconstitutionally apportioned the representatives because the population was nationwide instead of state by state. This gave eight states an extra representative, so there was more than 1 for every 30,000 people. Hamilton and Knox, on the other hand, said that the Constitution was unclear and they should defer to Congress on the bill’s constitutionality. Washington was wary of vetoing the bill because he feared it was siding with the South and would inflame tensions, but these concerns quieted and he returned the bill to the House with his veto message attached.

When the bill originally passed Congress, it did so with bare majorities in both chambers so a veto override was not feasible. So five days later Congress passed a revised bill complying with Washington’s concerns.

The veto power, like most of the President’s powers, comes not from raw force but from the restraint that has accompanied it. Most presidents are in the low teens for vetoes, and only five have had triple-digit vetoes. While President Franklin Roosevelt has the most, at 635 over his four terms in office, while seven didn’t veto a single bill. Vetoes are so often sustained that the first override didn’t take place until 1845.

To read more about Washington’s first veto, click the link below.